Nihilism is on the rise in postmodern society. Paul Bourget first adopted the term as a psychological concept in his Essais de Psycologie contemporaine , where he warned of the advent of a “great European disease“, defined as “a deadly weariness of living, a gloomy perception of the banality of all effort“.

Thus, what was already implicitly predicted by some 19th century authors and thinkers, mostly Russian, sons or more or less close relatives of the nihilistic anarchism that was already roaming their steppes – Lev Tolstoy, Fyodor Dostoevsky, Alexander Pushkin, Nicolas Gogol, Anton Gustave Flaubert, Søren Kierkegaard and, of course, Friedrich Nietzsche – has reached its peak in the utilitarian and productive model of life of the consumer society that today – we do not know until when – occupies us.

Already the literary production that followed in the 19th century offered us a robust consolidation of the predictions of these pseudo-prophets, finding in the anti-utopias of Fahrenheit 451 , 1984 , and above all, Brave New World , a diaphanous model of the days to come.

In the philosophical field, Nietzsche was succeeded by the already well-known, though perhaps not sufficiently read, Jean-Paul Sartre and Martin Heidegger, while in the diffuse terrain separating literature from philosophy, a hopeless Albert Camus published‘The Stranger‘ , while a certain Romanian author still unknown to the public, Émile Cioran, achieved the highest heights of cynicism and bitter vision of the world with works of remarkable literary talent, such as Of the Inconvenience of Being Born , Breviary of Rot or This Damned Self – laden with contempt, already empty of all hope – which had been gestating like an embryo in the bosom of the European mentality, and which achieved its state of maturity spurred on by the two world wars that virulently scourged the haughtiness and security of the average Westerner.

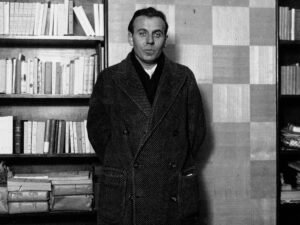

It is not the purpose of this article to elucidate the true historical and psychological origins of nihilism, since the hypotheses are lost in time, whether historical – it is not the overcoming of God commonly attributed to Nietzsche because it is easy to locate nihilist authors in previous epochs – or psychological – a multitude of variant manifestations, from Buddhist emptiness or even some medieval Christian mysticism, to the thanatic impulse theorised by psychoanalysis -, but rather to comment succinctly on an author, perhaps unknown among the leading authors of nihilism, and in particular on one of his works, whose circumstances of publication and the circumstances of publication are literature, deserve mention in the honourable list of thinkers of emptiness: His name is Louis-Ferdinand Céline.

It is not the purpose of this article to elucidate the true historical and psychological origins of nihilism, since the hypotheses are lost in time, whether historical – it is not the overcoming of God commonly attributed to Nietzsche because it is easy to locate nihilist authors in previous epochs – or psychological – a multitude of variant manifestations, from Buddhist emptiness or even some medieval Christian mysticism, to the thanatic impulse theorised by psychoanalysis -, but rather to comment succinctly on an author, perhaps unknown among the leading authors of nihilism, and in particular on one of his works, whose circumstances of publication and the circumstances of publication are literature, deserve mention in the honourable list of thinkers of emptiness: His name is Louis-Ferdinand Céline.

Who was hiding under this pseudonym? Céline, pseudonym of Louis-Ferdinand Destouches (Courbevoie, 1894 – Meudon, 1961), was a French doctor, later recycled into a novelist, who somewhat revolutionised the literary style of his native land with an aggressive and elegant prose, which surprised by breaking the moulds that governed the country’s literary status quo.

He took part in the First World War, where he was shot in the head and, although he survived, after the episode he was declared unfit for war service at the front. After his return to France, he travelled to Cameroon and England and worked as a doctor until, in 1932, he became popular with the novel Journey to the End of the Night (Voyage au bout de la nuit), which won the Renaudot Prize.

In it, we follow the adventures of Bardamu – a character who embodies the total disenchantment of life – in a series of journeys where the degradation of the external landscapes and scenery are merely footnotes to the protagonist’s state of inner degradation. Thus, the work that brought him recognition in literary circles was undoubtedly Journey to the End of the Night, a work whose individuality surpasses the whole offered by the mosaic of references, and from which I reproduce below a small fragment so that the reader can give an account according to his judgement of the author’s narrative talent, and at the same time discover what he is, while discovering what he is, a nihilist of our times:

lways I hadafeared that I would find myself empty, that I would have, in short, no compelling reason to exist. In the present and in the face of the evidence, I am convinced of my individual nothingness. In that environment, too different from the one I was used to, I felt instantly dissolved: I simply felt very close to non-existence. And so, as soon as they stopped talking to me about familiar things, I discovered that there was no longer any obstacle to falling into a kind of irresistible boredom, a sweet form of dreadful catastrophe of the soul. A disgust. At least the rubbish is not intended to last, nor to grow. In that respect, we are infinitely more wretched than shit, the rabid desire to persevere in our state is the most incredible torture. Our body, disguised as restless and vulgar molecules, constantly rebels against the atrocious farce of lasting. Our molecules, how rich they are! They want to lose themselves as quickly as possible in the Universe. They suffer from belonging exclusively to us, cuckolds of Infinity. Our misfortune is enclosed there, atomic, with our skin.